LAND REFORMS IN INDIA

Land reforms refer to a series of measures aimed at redistributing land, improving land ownership patterns, and enhancing agricultural productivity. They involve the regulation of ownership, tenancy, and cultivation of agricultural land to promote social justice and reduce inequality in rural areas. Land reforms are significant for rural development, poverty alleviation, and increasing agricultural output.

Land reforms refer to a series of measures aimed at redistributing land, improving land ownership patterns, and enhancing agricultural productivity. They involve the regulation of ownership, tenancy, and cultivation of agricultural land to promote social justice and reduce inequality in rural areas. Land reforms are significant for rural development, poverty alleviation, and increasing agricultural output.Historical Context

The British colonial administration introduced exploitative land tenure systems that created disparities in land ownership and resulted in rural distress:

- Zamindari System – Introduced by Lord Cornwallis in Bengal (1793), this system gave land ownership to Zamindars (landlords) who collected taxes from peasants. It led to the concentration of land in the hands of a few and exploitation of farmers.

- Ryotwari System – Introduced in Madras and Bombay presidencies, peasants were made direct landowners and responsible for tax payments. However, high tax rates and lack of security of tenure resulted in indebtedness.

- Mahalwari System – Introduced in the North-Western Provinces and Punjab, land revenue was assessed based on village land holdings, but the responsibility of payment was with village communities. It led to inequitable land distribution and exploitation by intermediaries.

Objectives of Land Reforms

After independence, land reforms were initiated to address the inequities and inefficiencies created by colonial land systems. The primary objectives were:

- Abolition of Intermediaries – To remove the Zamindari and other exploitative systems.

- Tenancy Reforms – To secure the rights of tenants and cultivators.

- Ceiling on Land Holdings – To ensure equitable distribution of land and prevent concentration in the hands of a few.

- Consolidation of Land Holdings – To improve agricultural productivity by eliminating fragmentation of land.

- Land to the Tiller – To promote ownership of land by actual cultivators and increase agricultural efficiency.

Land reforms were seen as essential for rural upliftment, reducing poverty, and promoting social justice, forming the foundation for India’s agrarian economy in the post-independence era.

Phases of Land Reforms

Land reforms in India can be divided into three distinct phases. The pre-independence phase (till 1947) focused on addressing exploitative systems like Zamindari, but reforms were limited due to colonial interests. The post-independence phase (1947–1991) prioritized abolition of intermediaries, land redistribution, tenancy reforms, and land ceiling laws to promote equity and rural development. The post-1991 phase (after economic liberalization) shifted focus toward market-led reforms, improving land records, digitization, and encouraging private sector involvement in land management.

1. Pre-Independence Efforts

Early efforts toward land reforms were influenced by growing peasant unrest and demands for equitable land distribution during the colonial period. Major movements and events included:

- Champaran Satyagraha (1917) – Led by Mahatma Gandhi against indigo planters, it highlighted the exploitative nature of colonial land tenure systems.

- Bardoli Satyagraha (1928) – Led by Sardar Patel, it was a tax revolt by farmers against the unjust land revenue system.

- Tebhaga Movement (1946) – A peasant movement in Bengal demanding two-thirds of the produce for sharecroppers instead of the prevailing one-half.

- Telangana Rebellion (1946–51) – A communist-led armed struggle against feudal landlords in the princely state of Hyderabad, demanding land redistribution and abolition of bonded labour.

These movements reflected deep-rooted dissatisfaction with colonial land policies and set the stage for post-independence reforms.

2. Post-Independence Reforms (1950s–70s)

The first wave of structured land reforms in independent India aimed to dismantle colonial land tenure systems and promote social justice. Key reforms included:

- Abolition of Zamindari (1950–60) – Intermediaries (zamindars) were removed, and ownership was transferred to tenants and cultivators. Over 20 million acres of land were redistributed.

- Tenancy Reforms – Focused on securing the rights of tenants, ensuring fair rent, and granting security of tenure. States like West Bengal and Kerala led the way through effective tenancy legislation.

- Ceiling on Land Holdings (1960s–70s) – State governments imposed ceilings on land holdings to prevent concentration of land in a few hands. Surplus land was to be redistributed to landless farmers.

- Consolidation of Land Holdings – Fragmented land parcels were consolidated to improve agricultural productivity. Punjab and Haryana made significant progress in this area.

- Bhoodan Movement (1951) – Led by Acharya Vinoba Bhave, it encouraged voluntary land donation by landlords for redistribution among the landless. Over 4 million acres were donated, though the movement lost momentum due to implementation challenges.

Despite initial success, land ceiling laws were poorly implemented due to political interference and bureaucratic inefficiencies.

3. Post-1991 Market-Oriented Reforms

Economic liberalization in 1991 marked a shift from state-led land reforms toward market-driven policies and privatization of land resources. Major trends included:

- Relaxation of Land Ceiling Laws – To encourage private investment in agriculture and rural infrastructure.

- Corporate Farming – Allowed private companies to lease large tracts of land for commercial farming.

- Land Acquisition and Rehabilitation Policies – The 2013 Land Acquisition Act provided fair compensation to farmers and ensured rehabilitation for displaced communities.

- Digital Land Records Modernization Programme (2008) – Aimed at creating a transparent and accessible land record system to reduce disputes and increase investment.

- Special Economic Zones (SEZs) – Large tracts of agricultural land were acquired for industrial development, leading to resistance from farmers and civil society (e.g., Nandigram and Singur protests).

The post-1991 phase saw increased privatization and corporatization of land, raising concerns about land alienation, displacement, and rural livelihoods.

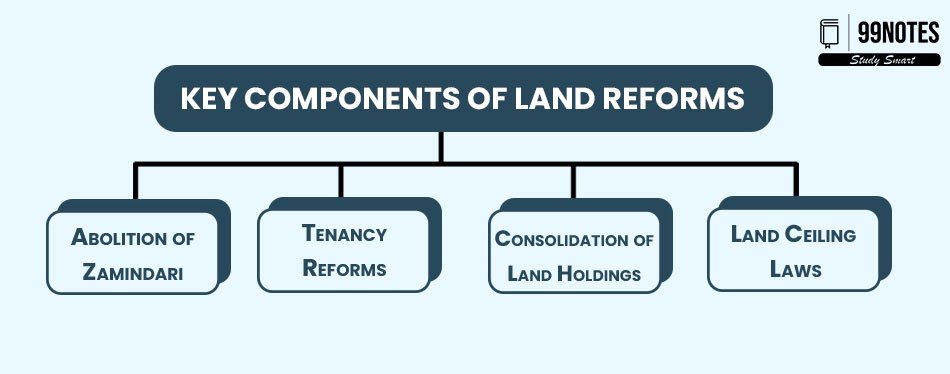

Major Components of Land Reforms (PYQ 2013)

Major Components of Land Reforms (PYQ 2013)

1. Abolition of Zamindari System

The abolition of the zamindari system was one of the earliest and most significant land reforms in independent India, aimed at dismantling the feudal land tenure system that concentrated land ownership in the hands of powerful landlords (zamindars). Under this system, zamindars acted as intermediaries between the British colonial government and the peasants, collecting rent and often exploiting tenant farmers. Post-independence, the government sought to eliminate this structure to empower actual cultivators and ensure social justice.

- The Zamindari Abolition Acts were passed in various states starting with Uttar Pradesh (U.P. Zamindari Abolition and Land Reforms Act, 1950), followed by Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and others. These laws aimed to transfer ownership rights from zamindars to the actual cultivators, ensuring that those who tilled the land became its rightful owners.

- Compensation was provided to the zamindars for the loss of their estates, but only in cases where they could prove legal ownership. Many large landlords attempted to evade the reforms by transferring land titles to family members or influential figures, thereby retaining control over the land indirectly.

- The abolition of zamindari was relatively successful in states like Kerala, West Bengal, and Tamil Nadu, where proactive political leadership ensured strong enforcement. However, in states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, powerful landed elites manipulated land records and used political influence to resist full implementation, limiting the overall impact.

- The reform also paved the way for future land reforms such as tenancy protection and land redistribution, forming the foundation for rural economic restructuring in post-independence India.

2. Tenancy Reforms

Tenancy reforms were introduced to protect the rights of tenant farmers and ensure that those cultivating the land could benefit from security of tenure and fair rental terms. Before independence, tenants often faced exploitation from landlords, including high rents, forced evictions, and lack of ownership rights. Post-independence, tenancy reforms aimed to address these issues by granting legal protection to tenants and ensuring equitable land access.

- The key objective of tenancy reforms was to establish a system where tenants were given security of tenure (protection from eviction), fair rent terms, and eventual ownership rights. Several states implemented tenancy reforms, but the extent of success varied depending on political will and administrative capacity.

- Operation Barga in West Bengal (1978), led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) under Jyoti Basu, was a landmark example of successful tenancy reform. It aimed to secure the rights of sharecroppers (bargadars) by legally recognizing them, capping the landlord’s share at 25% of the produce, and strengthening rural institutions like panchayats to enforce tenancy laws.

- Kerala’s tenancy reforms under the Kerala Land Reforms Act (1963) abolished landlordism and gave ownership rights to tenants, ensuring that land could no longer be held for absentee income generation. Tenants were also granted legal protection against arbitrary evictions, improving rural social and economic stability.

- In contrast, states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh witnessed limited success due to elite dominance and weak enforcement. Landlords often manipulated land records or forced tenants to become sharecroppers without legal rights, thereby maintaining control over land.

- While tenancy reforms contributed to greater rural empowerment and equitable land distribution, challenges such as land fragmentation, informal tenancy arrangements, and weak enforcement mechanisms limited their overall impact in many parts of India.

3. Land Ceiling and Redistribution

Land ceiling and redistribution were introduced to prevent the concentration of land in the hands of a few large landlords and to promote more equitable land ownership. The objective was to set an upper limit (ceiling) on the amount of land an individual or family could legally hold and to redistribute the surplus land to landless farmers and marginal cultivators.

- Land Ceiling Acts were enacted in most states during the 1960s and 1970s, setting specific limits on landholdings depending on the type of land (irrigated or non-irrigated) and the region. For example, in Punjab and Haryana, the ceiling was higher due to fertile land, while in states like Kerala and West Bengal, the ceiling was set lower to promote equity.

- Kerala and West Bengal achieved significant success in land redistribution through strict enforcement of ceiling laws and political commitment. In Kerala, over 1.5 million tenant farmers became landowners due to proactive redistribution measures. West Bengal’s Operation Barga ensured that sharecroppers received legal recognition and protection, strengthening their economic position.

- Bihar and Uttar Pradesh faced challenges in implementing land ceiling and redistribution due to elite dominance and political interference. Wealthy landlords often evaded ceiling laws through benami (proxy) ownership and by transferring land to family members. In many cases, local administrators were influenced by powerful landholding classes, weakening enforcement.

- Punjab and Haryana focused more on land consolidation rather than strict redistribution. This facilitated the Green Revolution by enabling mechanization and large-scale farming, but it also led to increased land concentration among wealthy farmers. Redistribution of surplus land was limited, but increased productivity and rural prosperity helped improve economic conditions.

4. Consolidation of Land Holdings

Consolidation of land holdings aimed to address the problem of land fragmentation, which reduced agricultural productivity and made mechanization difficult. Fragmentation resulted from inheritance laws and family divisions, leading to small, scattered land parcels that were inefficient to cultivate. The goal of consolidation was to merge these fragmented plots into larger, more manageable holdings to enable modern farming techniques and improve productivity.

- Implementation of Land Consolidation Acts was initiated in several states, with Punjab and Haryana achieving the most success due to strong political support and administrative efficiency. Landowners were persuaded to exchange their scattered plots for a single consolidated holding, which improved efficiency and allowed for better use of technology.

- Punjab and Haryana’s success in consolidation played a key role in the Green Revolution. Larger consolidated farms facilitated mechanization, irrigation, and the use of high-yield variety (HYV) seeds, boosting wheat and rice production. Increased productivity raised rural incomes and contributed to food security at the national level.

- Uttar Pradesh and Bihar attempted land consolidation, but efforts were hampered by elite dominance and weak administrative capacity. Powerful landlords manipulated land records and resisted consolidation efforts to maintain control over fragmented landholdings. Political interference further weakened enforcement.

- Kerala and West Bengal faced structural challenges in consolidation due to the prevalence of small landholdings and the political focus on tenancy reforms rather than consolidation. In Kerala, family divisions often led to further fragmentation, making it difficult to create large operational holdings. In West Bengal, the emphasis on protecting tenant rights under Operation Barga limited the scope for consolidation.

5. Bhoodan and Gramdan Movements

The Bhoodan (land gift) and Gramdan (village gift) movements were voluntary land reform initiatives launched by Acharya Vinoba Bhave in the early 1950s. These movements aimed to reduce land inequality and empower landless farmers by encouraging voluntary land donations from wealthy landowners. While Bhoodan focused on individual land donations, Gramdan aimed at the collective ownership of village land to promote cooperative farming and equitable distribution of resources.

Bhoodan Movement (1951)

The Bhoodan Movement began when Vinoba Bhave visited Pochampally village in Telangana, where landless farmers shared their hardships. In response, a landlord donated 100 acres of land, inspiring Bhave to launch a broader campaign for voluntary land redistribution. He traveled across the country, appealing to landlords to donate surplus land to the landless. By 1954, over 4 million acres had been pledged under Bhoodan. However, the actual distribution and legal transfer of ownership faced several challenges.

The Bhoodan Movement began when Vinoba Bhave visited Pochampally village in Telangana, where landless farmers shared their hardships. In response, a landlord donated 100 acres of land, inspiring Bhave to launch a broader campaign for voluntary land redistribution. He traveled across the country, appealing to landlords to donate surplus land to the landless. By 1954, over 4 million acres had been pledged under Bhoodan. However, the actual distribution and legal transfer of ownership faced several challenges.

Successes of Bhoodan

- Raised national awareness about land inequality and social justice.

- Helped reduce class tensions in some areas.

- Created moral pressure on landowners to act on social responsibility.

Challenges of Bhoodan

- The Bhoodan Movement lacked a clear and practical goal, with ambiguity about whether it aimed for land redistribution or a broader non-violent social revolution.

- It focused only on the landless, ignoring the semi-landless and marginal farmers, and often distributed unproductive or fallow land that offered little real benefit.

- The availability of surplus land was extremely limited, and the growing fragmentation of holdings due to population pressure made redistribution increasingly uneconomic.

- Most beneficiaries lacked the tools, resources, or support to cultivate the land effectively, raising serious concerns about rehabilitation and long-term viability.

- The movement’s opposition to mechanised farming and preference for small-scale agriculture was seen by some as outdated, and even likened by critics to forced collectivisation, leading to skepticism and resistance.

Gramdan Movement (1952)

The Gramdan Movement was a natural extension of Bhoodan, where instead of individual donations, entire villages would collectively donate land, putting it under cooperative management. The goal was to establish collective ownership, ensure equitable distribution, and promote cooperative farming. The first successful Gramdan village was established in Odisha, and the idea spread to Maharashtra, Odisha, and Tamil Nadu.

Features of Gramdan

- Villagers voluntarily placed land under collective ownership.

- Village committees managed land allocation and use.

- The movement promoted social harmony, equity, and shared responsibility.

- Gramdan Acts provided legal backing in some states to facilitate implementation.

Challenges of Gramdan

- Strong resistance from powerful landowning classes who opposed collective ownership.

- Political interference and lack of support from local elites.

- Inadequate legal enforcement and vague administrative mechanisms.

- Limited acceptance beyond a few regions; many villagers were reluctant to give up private ownership.

- Gramdan villages were isolated successes and did not scale widely.

Despite their limitations, the Bhoodan and Gramdan movements played a vital role in highlighting the issue of land inequality and influencing future land reform policies in India. They represented the Gandhian ideals of non-violence, trusteeship, and rural upliftment, and served as moral campaigns that inspired discussions on rural development and social justice in the early decades of independent India.

Successes of Land Reforms

Land reforms in India have achieved notable success in certain states, especially where political commitment and administrative efficiency were strong. Kerala and West Bengal stand out for their effective tenancy reforms, while Punjab and Haryana benefited from agricultural modernization linked to the Green Revolution.

- Successful abolition of landlordism – States like Kerala and West Bengal abolished the zamindari system and granted ownership rights to tenants. This empowered farmers, secured tenure, and reduced rural inequality, strengthening the agricultural base.

Effective tenancy reforms – Kerala’s and West Bengal’s tenancy reforms gave legal recognition and protection to tenants. Operation Barga in West Bengal secured sharecroppers’ rights, ensuring a fixed share of the produce and increasing rural income.

Effective tenancy reforms – Kerala’s and West Bengal’s tenancy reforms gave legal recognition and protection to tenants. Operation Barga in West Bengal secured sharecroppers’ rights, ensuring a fixed share of the produce and increasing rural income.- Redistribution of surplus land – In Kerala and West Bengal, surplus land was confiscated and redistributed to landless farmers. This reduced land concentration, increased rural employment, and improved economic security for small farmers.

- Increased agricultural productivity – Security of tenure and land ownership encouraged farmers to invest in better agricultural practices. In Punjab and Haryana, land consolidation and mechanization under the Green Revolution led to higher yields and rural prosperity.

- Improved rural income and poverty reduction – Land reforms in Kerala and West Bengal increased rural wages and improved living standards. In Punjab and Haryana, higher productivity and state support for cash crops boosted rural income and reduced poverty.

- Strengthened rural institutions – The empowerment of rural panchayats and cooperative farming initiatives in Kerala and West Bengal improved governance and rural decision-making. This enhanced local participation and increased accountability in land-related matters.

Failures of Land Reforms

Despite several attempts, land reforms in India have largely fallen short due to political resistance, weak enforcement, and social inequalities. Elite dominance, administrative corruption, and poor land records have undermined the intended goals of equitable land distribution and rural development.

- Incomplete abolition of zamindari – While zamindari was legally abolished, landlords retained control through proxy ownership and legal loopholes. Elite dominance in states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh allowed landlords to evade land ceiling laws, preserving rural inequality.

- Weak enforcement of land ceiling laws – Powerful landlords used political influence and benami transactions to bypass land ceiling limits. In Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, poor land records and administrative corruption further weakened enforcement, limiting land redistribution.

- Failure in tenancy reforms – Tenants were evicted or denied legal recognition despite protective laws. Political interference and lack of administrative capacity allowed landlords to reclaim land illegally, leading to rural insecurity and increased landlessness.

- Fragmentation of land holdings – Family divisions and inheritance laws caused excessive land fragmentation, reducing farm productivity and making mechanization difficult. Small and scattered landholdings increased input costs and reduced economies of scale.

- Political resistance and elite capture – Land reforms faced strong resistance from rural elites and landed castes (Bhumihars, Thakurs). Weak political will and vote-bank politics prevented effective land redistribution, maintaining social and political dominance.

- Limited impact on rural poverty – Due to weak enforcement and loopholes, land redistribution was minimal in many regions. Persistent landlessness and rural distress contributed to agrarian unrest and the rise of Naxalite movements in affected areas.

| Conflict Between Land Reforms and Fundamental Rights in India |

|

Land reforms in independent India aimed to address agrarian inequalities and empower rural communities but faced legal challenges due to conflicts with fundamental rights. The abolition of the zamindari system and land redistribution were contested under Article 19(1)(f) and Article 31, which protected the right to property. • First Amendment (1951): Added the Ninth Schedule to protect land reform laws from judicial review. The resolution of the property rights issue allowed the government to implement land reforms more effectively, ensuring social justice and economic equality. |

Comparison of State-Level Land Reforms

| State | Successes | Challenges |

| Kerala | Successful land redistribution, tenant rights secured, reduction in rural poverty, improved human development indicators. | Small farm sizes led to operational inefficiency, difficulty in mechanization, dependence on cash crops exposed farmers to market risks. |

| West Bengal | Operation Barga secured tenancy rights, increased agricultural productivity, reduced rural poverty. | Fragmentation of landholdings, political interference, over-reliance on food grains limited crop diversification. |

| Bihar | Abolition of zamindari system (on paper), attempts at surplus land redistribution. | Political dominance of landlords, evasion of ceiling laws through benami ownership, weak administrative enforcement. |

| Uttar Pradesh | Zamindari Abolition Act abolished intermediaries, partial success in securing tenancy rights. | Influence of dominant castes in rural politics, manipulation of land records, poor irrigation infrastructure. |

| Punjab | Consolidation of land holdings, agricultural modernization through Green Revolution, high rural prosperity. | Increased land concentration among wealthy farmers, groundwater depletion, rising debt burden. |

| Haryana | Successful consolidation of holdings, mechanization, shift toward cash crops and dairy farming. | Environmental degradation, increasing input costs, groundwater depletion. |

Land Reforms and Economic Liberalization

The economic liberalization initiated in 1991 under Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao and Finance Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh marked a fundamental shift in India’s land reforms from state-led redistributive policies to market-driven approaches. While these reforms boosted agricultural productivity and economic growth, they also created challenges related to land acquisition, rural distress, and social inequalities.

- Shift from State-Led to Market-Driven Reforms: Post-1991, the focus of land reforms shifted from redistributive justice to enhancing market efficiency. The government reduced direct control over land distribution, encouraging private sector participation and market-based land transactions.

- Economic Liberalization and Land Policies: The liberalization era introduced the L-P-G (Liberalization, Privatization, Globalization) model, which influenced land policies. Privatization allowed large corporations to acquire agricultural land for commercial use, while globalization increased foreign interest in India’s land market.

- Rise of Commercial and Contract Farming: Economic liberalization facilitated the growth of contract farming and commercial agriculture. Corporations began entering into agreements with farmers for assured supply chains, but farmers became vulnerable to price fluctuations and unequal bargaining power.

- Challenges in Land Acquisition for SEZs and Industries: The SEZ Act (2005) allowed for large-scale land acquisition for industrial projects, often leading to displacement and inadequate compensation for farmers. Protests in Nandigram and Singur highlighted these tensions.

- Urbanization and Infrastructure Development: The push for urbanization and infrastructure development post-1991 led to rapid land conversion from agricultural to industrial and residential use. Projects like the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor and Yamuna Expressway faced opposition due to environmental and displacement concerns.

- Impact on Social and Economic Inequality: While economic liberalization increased land productivity and infrastructure, it also widened wealth gaps. Corporate ownership of land increased, while small farmers faced landlessness and market vulnerability.

Post-1991 land reforms boosted productivity and industrial growth but increased rural distress and social inequality. The challenge lies in balancing economic growth with protecting the rights of marginalized communities and ensuring fair compensation for land acquisition.

Contemporary Challenges in Land Reforms

Despite historical efforts to improve land ownership and agricultural productivity, land reforms in India face ongoing challenges due to legal, administrative, and socio-economic issues. Urbanization, industrialization, and infrastructure development have further complicated land governance.

Land disputes and conflicts over ownership: It remain one of the most common causes of civil litigation in India. A significant portion of the pending cases in Indian courts are related to land ownership and property rights. The lack of clear land titles, outdated land records, and fraudulent transactions have contributed to these disputes.

Land disputes and conflicts over ownership: It remain one of the most common causes of civil litigation in India. A significant portion of the pending cases in Indian courts are related to land ownership and property rights. The lack of clear land titles, outdated land records, and fraudulent transactions have contributed to these disputes.- Ambiguities in land ownership: It arise from incomplete land surveys, inheritance conflicts, and fragmented landholdings due to family divisions. Encroachment and illegal occupation of government and forest land, along with poor coordination between revenue departments and local authorities, have worsened the problem. The Bhojpur conflict in Bihar highlighted how caste-based divisions and elite dominance over landownership continue to fuel rural unrest.

- The colonial-era Land Acquisition Act of 1894: This act allowed the state to acquire land for public purposes with minimal compensation, leading to exploitation and displacement. The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (LARR) Act, 2013 introduced reforms, including higher compensation, consent requirements, and rehabilitation measures, but its implementation has been inconsistent due to political and corporate influence.

- Delays in acquiring land: It arisesdue to legal challenges and resistance from landowners have affected infrastructure and industrial projects. Inadequate rehabilitation measures, political and corporate interference, and increasing resistance from tribal communities over forest land acquisition have further complicated the process. The Niyamgiri case in Odisha highlighted the conflict between industrial development and indigenous rights.

- Digitization of land records: Under the Digital India Land Records Modernization Programme (DILRMP) launched in 2008 aimed to improve transparency and reduce litigation. Key components include computerization of records, digitization of cadastral maps, and integration of land records with revenue and judicial systems. However, incomplete records, data mismatches, and corruption have hindered progress.

- Poor land governance: Poor land governance has made it difficult for farmers to access institutional credit due to unclear land titles. Government compensation for land acquisition is often delayed due to legal disputes, and illegal land transfers and encroachments remain widespread. Vulnerable communities continue to face exclusion from land ownership benefits.

Land reforms in India face persistent challenges due to unresolved disputes, inadequate land acquisition policies, and poor land governance. Effective implementation of legal reforms, digitization, and community participation are essential to address these issues.

Conclusion

Land reforms in India have played a transformative role in reducing agrarian inequality, securing tenant rights, and improving agricultural productivity. While the abolition of zamindari and tenancy reforms marked significant progress, challenges like unequal land distribution, insecure tenure, and weak implementation persist. Strengthening land rights, promoting digitization of land records, and ensuring equitable land acquisition practices are essential for addressing these gaps.

A more integrated and transparent approach, combined with legal reforms and participatory governance, is crucial for making land reforms more effective and sustainable in promoting rural development and social justice.

Related FAQs of LAND REFORMS IN INDIA

Land reforms aimed to abolish exploitative systems like zamindari, secure tenant rights, redistribute land to reduce inequality, improve agricultural productivity, and empower rural communities through ownership and legal protection.

Kerala and West Bengal achieved notable success. West Bengal’s Operation Barga secured tenant rights, while Kerala’s reforms redistributed land and abolished landlordism. Both states saw reduced poverty, better governance, and stronger rural institutions.

Post-1991, the focus shifted to market-led reforms. This included relaxed land ceilings, corporate farming, and increased land acquisition for industries. While this boosted productivity, it also raised issues of displacement, inequality, and land alienation.

Major issues include unclear land titles, digitization delays, legal disputes, and poor compensation in land acquisition. Effective governance, legal clarity, and community participation are crucial to make land reforms more impactful and inclusive.

In many states, elite dominance, benami transactions, and political interference weakened implementation. Tenants were often evicted without legal protection, and land ceiling laws were evaded by landlords, limiting redistribution efforts.

![Swadeshi Movement (1905): Overview, Causes &Amp; Impact [Upsc Notes] | Updated December 29, 2025 Swadeshi Movement (1905): Overview, Causes & Impact [Upsc Notes]](https://www.99notes.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/swadeshi-movement-featured-66698a5e632b7-768x500.webp)

![Maratha Empire: History, Rulers, War &Amp; Administration [Upsc Notes] | Updated December 29, 2025 Maratha Empire: History, Rulers, War & Administration [Upsc Notes]](https://www.99notes.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/maratha-empire-featured-768x500.webp)