Sculptures

The word for sculpture is ‘Shilpa,’ which means to ‘create.’ Sculpture was the favoured medium of artistic manifestation on the Indian subcontinent. It signifies the traditions, forms, and styles of the civilisations of the Indian subcontinent.

Many styles and traditions flourished throughout India over the succeeding centuries. By the 9th–10th centuries AD, Indian sculpture had reached a form that has lasted with little change up to the present day.

Earliest Sculptures:

- Earliest Sculptures:

- Mauryan Era

- Free Standing Sculptures

- Pillars

- Relief Carving

- Post Mauryan Sculptures

- Characteristics of Carvings:

- Gandhara, Mathura and Amrawati School of Art

- Hellenistic influence in Gandhara Art

- Development in Mathura Art

- Gupta Sculptures:

- Sculptural Features of Ajanta Caves

- Art in Early Medieval times

- Temple Sculptures – Regionalisation

- FAQs related to Sculptures

Stone is the most rudimentary form of material out of which sculptures can be shaped. As soon as hardness in metals was achieved, i.e. Bronze was discovered Indians started making sculptures.

The earliest sculptures found in India belong to the Indus Valley Civilisation.

Apart from the stone sculptures, we find a wide variety of Terracotta and Bronze sculptures, that we have covered in a separate chapter.

After the Harappan period, we do not find any significant sculptural finds till the start of 2nd urbanisation phase of India during the Mahajanapada period. In the Pre-Mauryan and Mauryan Periods. The quality of the stonework and the sculptures matured rapidly, which eventually led to the development of complex temple art all over India.

Mauryan Era

During the Mauryan age, the stone-craft matured to the extent that we find a separate class of skilled craftsmen. The literature of the period mentions the guild of artisans who worked on the projects of Asoka.

Features of Mauryan sculpture

- Material used: There was a departure from the use of wood, sun-dried brick, clay, ivory and metal to that of stone in gigantic dimensions. They mostly used Sandstones.

- Surfaces: The stupa railings, gateways, and chaitya facades all bear the details of ornamentation, which are a copy of the wooden prototype.

- Themes: There are secular as well as religious themes. Ashoka, for example, made his own efforts to articulate Buddhism in stone.

Understanding Mauryan sculpture

Sculptures in the Mauryan times can be studied under three categories:

- Free-standing sculptures; For example, idols of Yaksha and Yakshinis.

- Mauryan Pillars

- Sculpting on the surfaces. For example, The front half of an elephant carved round from a live rock in Dhauli in Odisha, and the monolithic railing at Sarnath.

- The remnants of the royal palace and the city of Pataliputra are there.

Free Standing Sculptures

We find Yaksha, Yakhinis and animals, pillar columns with capital figures, and rock-cut caves belonging to the 3rd century BCE have been found in different parts of India.

Ring stones and Disc stones

Along with all the monumental works of art and architecture produced under royal patronage, there were some works of art depicting folk deities and beliefs like mother goddess and flower worship, carved very minutely on ring stones, which are round polished stones less than three inches in diameter having a central hole.

Some of them do not have holes. These are recognised as disc stones. On their surface, the motifs of lotus, palm trees, birds and other animals are carved.

Yaksha-Yakshini

The most significant sculpture of the Mauryan age is Yaksha-Yakshini.

Two statues of Yaksha are excavated from Patna. A colossal statue of a Yaksha (7 feet high) bearing an inscription in Ashokan Brahmi script at Parkham was excavated near Mathura.

Didarganj Yakshini,

- Patna: Mauryan Age;

- Tall, well-proportioned, free-standing sculpture, holding a Chauri (flywhisk) in round made in sandstone with a polished surface.;

- The left hand is broken. The face has round, fleshy cheeks, the neck is relatively small; the eyes and nose lips are sharp.

- Necklace beads are in full round, hanging to the belly. A tightened garment creates the effect of a bulging belly. Every fold of the garment on the legs is shown by protruding lines clinging to the legs creating a somewhat transparent effect. The middle band of the garment falls to the feet. Heaviness in the torso is depicted by heavy breasts.

- Back is equally impressive. Hair is tied in a knot at the bare back. Drapery at the back covers both legs.

| What are Yaksha and Yakshinis? |

| The traditional Indian beliefs identify Yaksha and Yakshini, respectively, as God and Goddess of material plenty and physical welfare.

The term Yaksha refers to a broad class of nature spirits, usually benevolent, but sometimes mischievous and sexually aggressive or capricious caretakers of the natural treasures hidden in the earth and tree roots. Yakshini or Yakshi are Female counterparts of the Yakshas. |

Pillars

The great Ashoka started the practice of erecting pillars, using them to mark his edicts. Such practice was first started by the Achaemenian Empire of Persia in around 500 BC.

Prominent of Ashokan Pillars

The surviving examples do not present a unified picture but vary greatly in the type of stone, polish or lack of polish, proportions, treatment of sculptural details, dowelling techniques, and even methods of insertion into the earth. Scholars have tried to understand the symbolism inherent in the columns.

- They are made of sandstone, which was quarried at Chunar (Near Mirzapur).

- The whole pillar including its capital was carved out of one single slab.

- They have a lustrous polish and could have been copies of Mauryan wooden pillars.

- The Ashokan pillars do not have a base and are directly rooted in the soil without a foundation or a base.

Comparison with Achaemenian Pillars

It is believed that Mauryas’ came into indirect contact with Achaemenid (Persian) art and culture and adopted this practice.

There are various reasons to believe that Mauryans were influenced by the Persians.

- Lions crafted by Indians bear similar resemblances to the lions sculpted earlier by the Persians.

- Similarity in other constructions as well. For example – Pillared Hall at Kumrahar also compares well with the Hall of Hundred Columns erected at Persepolis by Darius the Great.

Further, both use different kinds of sandstones, as carving is easy on such stones.

However, there is a marked difference between the two types of pillars:

| Persian Pillars |

Ashokan Pillars |

|

| Empire | Achaemenian Empire of Persia | By Mauryans under Ashoka |

| Timeline | 6-7th century BCE onwards | 3rd Century BCE |

| Type | Part of larger architecture (state buildings) such as halls and palaces. | Free-standing structure, generally constructed near Stupa or Monastery. |

| Construction | Constructed piece by piece, i.e. by placing one cylindrical drum over another with the same diameter. | Monolithic in nature: Carved out of a single stone slab, with tapering shafts. |

| Surface | Rigid Surface | Smooth Surface |

Structure of Ashokan Pillar

The pillar itself originally consisted of five component parts:

- Shaft: The Shaft itself is often huge. For example, at Vaishali, it is more than 18m tall. At Sarnath, it is now broken into many pieces. The shafts often carry Ashokan edicts too.

- Bell Capital: The capital is joined to the tapering end of the shaft. The capital is in the shape of an inverted lotus (often referred to as the bell capital).

- Abacus: On top of it is an abacus (platform). On the Sarnath Pillar, it is in the shape of a drum carved with four animals alternating with four chakras (24 spokes) proceeding clockwise, Circular abacus is carved with the figures of a horse, a bull, a lion and an elephant in vigorous movement. Each element is voluminous(3-D) despite sticking to the surface. It finally supports an animal carved in round.

- Capital figure: the figures of four majestic addorsed lions, seated on a circular abacus.

- Crowning element: Dharamchakra, a large wheel, was also a part of the Sarnath pillar, which is now missing.

Ashokan Pillar Edits

These pillars were probably designed for two purposes, one, to carry Ashoka’s message (Edicts) and two, to portray the strength of the empire.

- The columns that carry Ashokan inscriptions are those of Delhi-Mirat, Allahabad, Lauriya-Araraj, Lauriya-Nandangarh, Rampurva, Delhi-Topara, Sankisya, Sanchi and Sarnath.

- The non-edict bearing columns include those of Rampurva, BasarhBakhira and Kosam.

- Columns bearing dedicatory inscriptions have been found at Rummendei and Nigali Sagar. Of these, the capitals of Lauriya-Nandangarh and Basarh-Bakhira are in situ. Those of Rampurva, Sankisya, Sarnath and Sanchi have been recovered in a damaged condition.

It is interesting to note that Ashoka himself called this pillar Sila Thmabha in Prakrit (or Shila Stambha in Sanskrit), i.e. stone pillars or Dhamma Thambha (Pillar of righteousness).

One must cover Chapter 14 of the Ancient India book to understand the historical context of Ashoka’s edicts.

Important Ashokan Pillars

Allahabad pillar too had a lion capital till the 19th century, which is now lost.

From the reading of inscriptions at Rupnath and Sahasram, it is clear that some of the pillars that carry Ashoka’s inscriptions could be pre-Mauryan in age, hence, not particularly Buddhist in character. Some were erected by Ashoka himself as Dharmastambhas.

Relief Carving

Carvings on the surface are called as Relief carvings.

1. Dhauli Elephant

At Dhauli (Bhubaneshwara, Odisha), there is a rock sculpture of the front part of an elephant.

It has a heavy trunk that curls gracefully inwards. His right front leg is slightly tilted, and the left one is slightly bent, suggesting forward movement. Its naturalistic stance and powerful portrayal in stone are very impressive and give the feeling that the elephant is walking out of the rock.

2. Mauryan Caves:

The Mauryan caves often show a carved Façade referred to as the chaitya arch, semi-circular in shape giving it a hut-style façade.

The Mauryan caves often show a carved Façade referred to as the chaitya arch, semi-circular in shape giving it a hut-style façade.

- For example, the Lomas Rishi cave entrance is sculpted in high relief with a row of elephants moving towards the stupa emblem, indicating that the cave was probably dedicated to the Buddhists.

Further, we find a polished fragment of a monolithic railing at Sarnath assigned to the Mauryan period. It is made of polished Chunar sandstone.

Features of Mauryan Relief carvings

- Shallow Depth of Carving: Images do not protrude much out of the picture plane, but still are able to give a perception of depth.

- Polishing: The exteriors of the caves are very plain. However, the interiors are polished to a high degree.

Post Mauryan Sculptures

Several rock-cut caves in the Deccan demonstrate advancement in sculptural art in this age.

However, the best-found examples of the sculptures and carvings in the Post Mauryan Period are found at Torana or the Railings of Stupas.

Sanchi Stupa is one of the most well-preserved. It compares well with the Bharhut Stupa railing (1st-2nd century BCE). In Bharhut, we have the oldest preserved carvings on railings wherein the plinth or the ‘alambana’, the uprights or the ‘stambhas’, the horizontal bars or the ‘suchis’ and the coping stone or the ‘ushnisha’ have all been carved from a single monolithic stone.

Characteristics of Carvings:

Initially, carvings were simple, but the level of refinement improved drastically in the Shunga period. The following characteristics can be noted from this period:

- Fewer Characters: In Barhut Railing, narrative panels are shown with fewer characters but as time progresses, such as in the railings of Sanchi Stupa (built by Shungas and Satvahanas), apart from the main character in the story; Others also start appearing in picture space. Only single figures of Yakshas and Yakshinis are shown in Barhut Stupa.

- The availability of space is utilised to the maximum by sculptors.

- Shallow and flat carving: projection of hands and feet was not possible; hence, hands are folded, clinging to the chest and figures show the awkward position of feet.

- There is a general stiffness in the body and arms.

Carvings found on toranas indicate that such carvings were originally made of wood because such kinds of carvings could be carried out easily on wood.

Gradually, visual appearance was modified by making images with deep carvings, pronounced volume and a very naturalistic representation of human and animal bodies. Case in point, carvings at the Stupa I of Sanchi, whose Torans and Vedika were sculpted on a later date.

Themes:

| Symbols | Meaning |

| Elephant | Conception |

| Lotus | Birth |

| Horse | Renunciation |

| Footmarks | Leaving home |

| Empty Seat | Buddha in Meditation |

| Peepal Tree | Enlightenment |

| Wheel | Dharmachakrapravartana |

| Stupa | Death – Mahaparinibbana |

- Scenes related to previous birth stories of Buddha (Jataka stories) have been portrayed. For example, Processions of animals and human beings joining to visit Buddha are portrayed, which indicates that Buddha was very popular among them.

- Representation of Buddha was generally through symbols initially.

- Later in Gandhar and Mathura Traditions Buddha was widely represented in human forms.

Motifs employed under Buddhist Art:

It is believed that many people who turned to Buddhism enriched it with their own pre-Buddhist and even non-Buddhist beliefs, practices and ideas, and therefore we find several pre-Buddhist motifs in Indian Art. For example: –

- Folk deities such as Yaksha and Yakshini (Yakshi) were also prevalent in stupas.

- Shalabhanjika Motif: Beautiful women swinging from the edge of the gateway, holding onto a tree represent a Shalabhanjika; According to popular beliefs this was a woman or a Yakshi whose touch caused trees to flower and bear fruit.

- Elephant: depicted Strength and Wisdom;

- Gajalakshmi: God of fortune; Associated with elephants.

Gandhara, Mathura and Amrawati School of Art

The sculpture of the Lord Buddha emerged during the first few centuries C.E. in two major centres of Indian art during the Kushana period. One centre was the ancient region of Gandhara, and a second area was associated with Mathura.

These art forms existed between the 2nd and 5th century C.E. in the Indian subcontinent with their separate identity.

| Topic | Gandhara styles | Mathura styles | Amaravati styles |

| Influence | Greek / Hellenistic Influence. | Indigenous. | Indigenous. |

| Types of Material Used | Black Schist / Bluish – Grey sandstone.

Bodhisattva with moustache |

Spotted Red sandstone, Yellow sandstone

Headless statue of Kanishka |

White Marble. |

| Religious influence | Mainly Buddhist Sculptures | All three religions (Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism) were visible;

Shiva is represented through Linga, and Sculptures of Mahavira and Vishnu are also covered. |

Mainly Buddhist. |

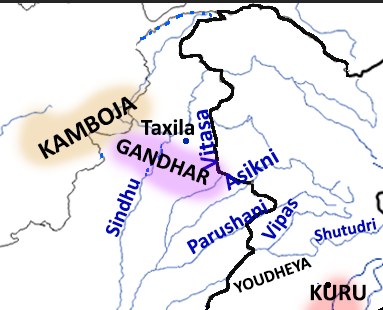

| Areas spread | Kushan Capital – Purushpur (Modern Peshawar)

Mainly flourished around the Northwest Frontier. Other centres: Taksha-shila (Taxila), Jalalabad, Hadda, Bamaran and Begram. |

Kushan Capital – Mathura

Mainly flourished around Mathura, Kankali-Tila (in Mathura) and Sonkh. Other Centres: Sarnath and Kausambi.

|

Ikshavaku of Vaijaipuri (Nagarjunkonda)

Mainly around lower Krishna-Godavari Plains. Other Centres: Vengi, Jagayyapetta, Goli, Amaravati, Bhattiprolu, Nagarjunkonda etc.

|

| Features of Sculptures | Buddha is depicted in the human form for the first time. It closely resembles Mahayana Buddhism, so the main theme was Lord Buddha and Bodhisattvas.

Features of Buddha:

Gandhara Buddha, 2nd cent. |

The female figures at Mathura, are carved in high relief on the pillars and gateways of both Buddhist and Jaina monuments.

Features of Buddha

Katra Buddha – 2nd Cent. |

Stories of previous births of Buddha – both in human as well as animal form are well described.

Features of Buddha

Other Figures:

Relief Sculpture from Amaravati Maha Stupa |

| Royal Patronage | Both Shakas and Kushanas were patrons of the Gandhara School of Art.

It flourished from about the middle of the 5th century B.C. to about the 5th century A.D. |

Mathura art developed during the Mauryan period (during Shungas) and peaked during the Guptas (AD 325-600).

|

Satvahana & Icchavakus. |

| Prominent examples | Bamiyan Buddha statue in central Afghanistan. | Parkham Yaksa, Seated Kubera etc. | Taming of an Elephant by the Buddha. |

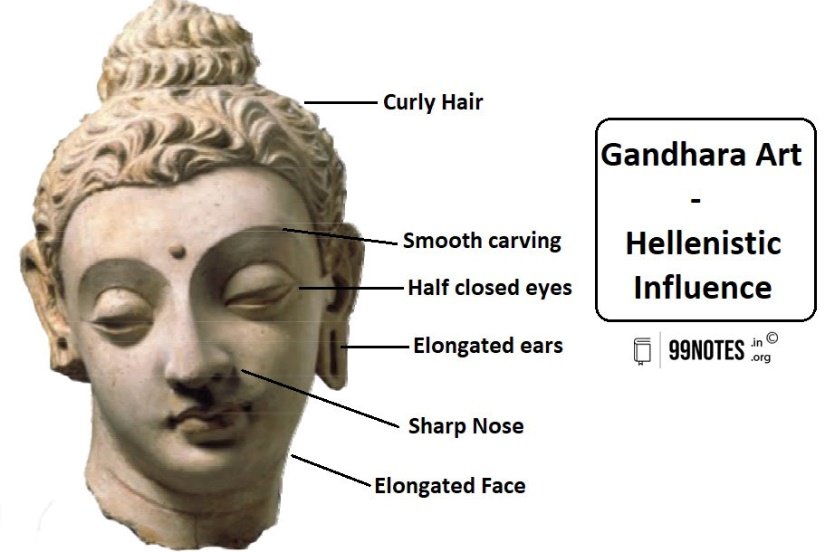

Hellenistic influence in Gandhara Art

The Hellenistic period refers to the Greek period after the death of Alexander till the arrival of the Roman empire, i.e. period between the 4th to 1st Century BCE.

The influence of the Greeks on Indian art is referred to as the Hellenistic influence. The Gandhara, being at the cross junction with the West was influenced by it first and is thus also known as Greco-Buddhist Art.

The Greeks first came to India with Alexander. Later settlements made by him in Central Asia, Persia and India continued to be centres of Greek Art.

Greeko-Bactrian Influence

- Hairs: Greeks generally make wavy hairs. Even the style of tying knots is wavy.

- Unna a dot in the middle of the eyebrows, representing the 3rd

- Dress: Garments with thick pleats cover both shoulders.

- Body: A muscular body (with less amount of flesh), with a large forehead and long ears, is often represented.

- Introduction of Greek God: Buddha is often shown in the protection of the Greek God Hercules standing by his club.

Apart from these, Gandhara art was also influenced by regional central Asian Kingdoms which got connected via Greek rulers.

Central Asian Influence:

- Type of Stone used: Use of Dark Schist, Green Phyllite and Grey Blue Mica Schist.

- Procedure: Stones were first shaped and then covered with plaster.

- Halo: It was similar to Persian reverence to God – a simple Halo.

- Dress: Figures have conical caps – Scythian Caps.

- Inscription: Kharosthi script is found along with circumambulatory corridors around the temples.

Further, various advancements were introduced in other aspects of art as well. For example, the minting of coins started for the first time during the Greek period. Such aspects of change in lifestyle are discussed in Chapter 10 of the Ancient India textbook.

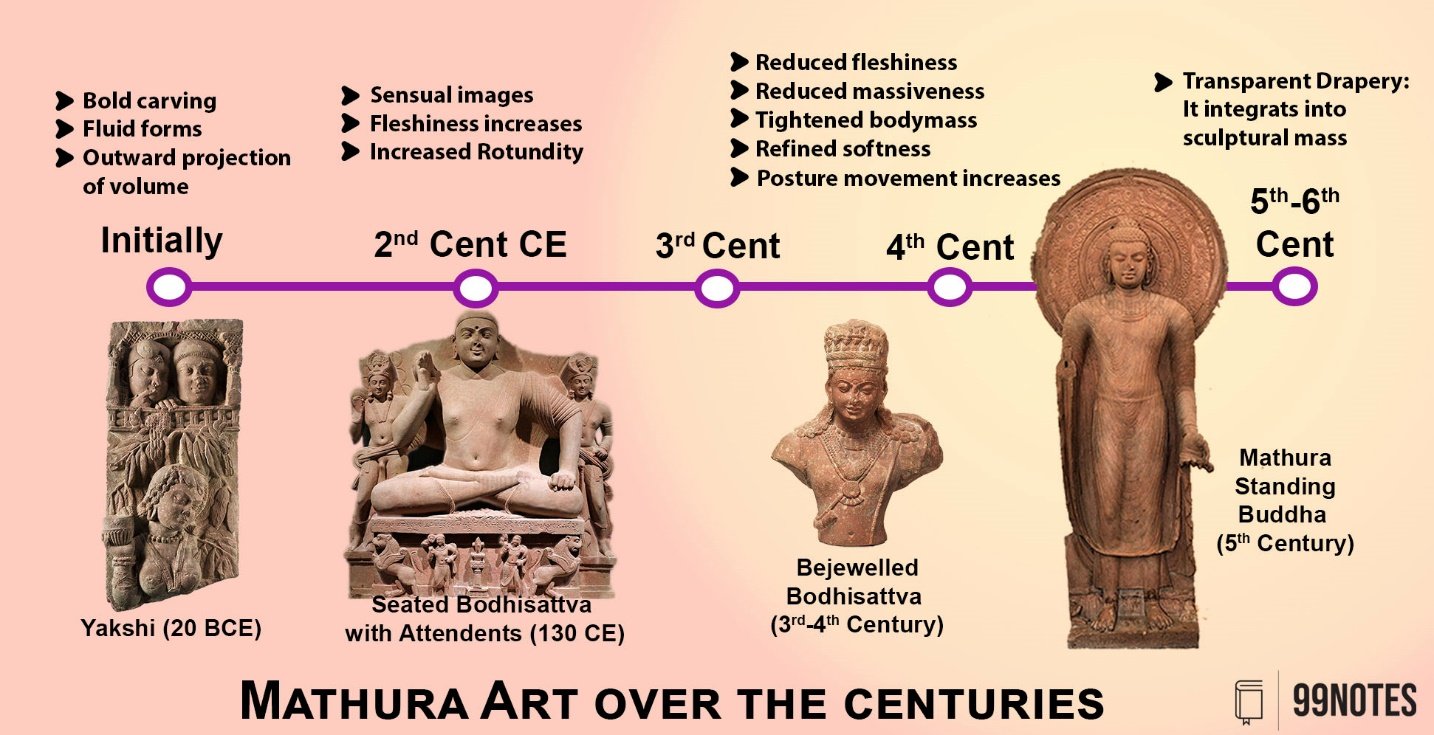

Development in Mathura Art

Over the centuries, several changes in the sculptural style emerged.

Comparison between Mathura and Sarnath centres:

By the Gupta age, the Mathura art blossomed and several regional centres like Sarnath and Kaushambi emerged. It is interesting to note the difference between classical Mathura sculptures and the Sarnath Sculptures of this time.

| Katra Tila Buddha (2nd cent CE) | Sarnath Buddha (5th cent CE) |

|

Spotted red Sandstone |

Chunar sandstone |

| The face is round and smiling. The face along with the head is shaven, with a knot (Ushanisha). | Roundness of cheeks reduced; Eyes are half-closed; lower lip is protruding. Ushanisha with circular curled hairs; |

| Padmasana Posture, Right hand in Abhayamudra and left hand on the thigh. | Padmasana Posture and Hands in Dhammachakra Mudra. |

| Bodhisattvas stand as attendants: Padmapani holds lotus and Vajrapani holds Vajra i.e. thunderbolt; Both wear crowns; | The panel below the throne depicts a chakra (wheel) in the centre and a deer on either side with his disciples. |

| Body: High in flexibility and the Belly Bulge is sculpted with controlled musculature. | The body is slender and slightly elongated; Outlines are delicate & rhythmic; |

| In Mathura Style, drapery depicts folds generally covering only one shoulder. | Images have plain transparent drapery covering both shoulders, as seen here too. |

| Halo has very little ornamentation. | The halo around the head is profusely decorated with the plain centre. |

Gupta Sculptures:

The Gupta period, known as the Golden Age, saw improvement over the Kushan style. The Mathura art flourished and was touched with refinement in all aspects.

- Regional Centres of Mathura Art: Samath and Nalanda progressed as the main centres in the north.

- Sculptures in Stupas: such as in the Dhamek stupa at Samath.

- The other places where we noticed Gupta sculptures are the Vishnu sculptures in Udayagiri Caves, and the Buddhist caves in Ajanta.

- Sculptures in temples: For example, in the Dasavatara Vishnu Temple in Deogarh. We have already learned that the sculptures of Dwarpal, Mithun, and the river goddesses also became popular in temple architecture.

Features of Gupta age sculptures:

There were little variations in centuries leading from the Later Mauryan age to the Gupta.

- We still see slender images. Even though there is protrusion outside the picture plane to give a 3D effect, but still the movement of figures is limited.

- The drapery became transparent.

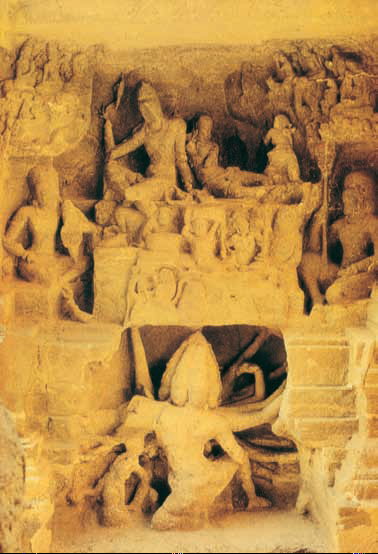

Sculptural Features of Ajanta Caves

Ajanta caves (2nd century BCE to the 7th century CE) are excellent for the study of Indian classical art of sculptures and architecture. These were patronised by Satavahanas, Vakatakas, and Guptas, and were later abandoned. Here we can see the advancements in the art as time progressed till the Gupta period.

In Ajanta Caves, events are grouped according to geographical locations: which is indicated by using outward architectural bands. For example, in Chhaddanta Jataka (cave 10) painting events that happened in the jungle are separated from events that happened in the palace.

The entire hall of Cave 26 is carved with the Buddha image of Mahaparinibbana (the biggest one). Its Mara Vijaya sculptural panel is the largest one at Ajanta. It is sculpted near the colossal Buddha image of Mahaparinibbana.

- Surfaces: The Façade is generally decorated with Buddha and Boddhisattva images.

- 3D Effect: The architectural setting is simple and the arrangement of figures is delineated in a circular form to create 3-D and special effects.

- Eyes: Half-closed, elongated eyes are employed.

- Few Sculptures are colossal.

- Paintings are very well integrated with the sculptures in the later phase.

We find similar features employed in the other caves of this age too. Such as in Bhaja, Pitalkhora, Bagh, Kondana, Karla, Bedse and Nashik caves.

The enormous rock-cut chaitya hall was excavated from Karla’s cave. The chaitya hall is decorated with human and animal figures, showing movement in space. The façade is a stone screen wall. Chaitya is of apsidal vault-roof type with pillared halls and a stupa at the back.

Few caves had developed elements similar to the temple architecture. For example, Pitalkhora cave features statues of elephants, gatekeepers, and Gaja Lakshmi.

Art in Early Medieval times

In the Early medieval times, sculptural art in India had already been more than a millennium old. Several styles developed under the Buddhist, Hindu and Jaina patronage merged, leading to the emergence of several regional styles.

Sculptures in Caves

Ellora Cave is representative of this age. We see similar sculptures in Elephanta.

- Vigorous movements in picture space can be seen.

- Complexity of Sculptures: The sculptural volume is quite heavy and strikingly protruding, and considerable sophistication can be seen in it. Sculptures have protruding volumes that create deep recession in the picture space.

- Slenderness in the body, with stark dark and light effects, is the most important feature of these sculptures, especially in the Elephanta caves.

- Remarkable qualities of surface smoothness, elongation, and rhythmic movement.

- Diversity: Ellora Caves are the most diverse caves in India, as the Sculptors belonged to guilds from several places like Vidarbha, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

- Elements from Temple architecture: The river goddesses Ganga and Yamuna sculptures at the entrance are common.

- The icons of Yaksha and Yakshinis are generally replaced and instead, we find Dwarpals and Mithuns.

- Monumental Size: Sculptures at Ellora are monumental. For example, the Kailash Leni temple is carved out of a single rock in Vesara Style Architecture. Although, Brahmanical caves are less massive;

- Painting and Fresco: All caves were plastered & painted but nothing visible has now left.

Emerging Popularity of Brahmanical Themes

We find many caves dedicated to Shaivism in Ellora, but the various forms of both Shiva and Vishnu according to the Puranic narrative are depicted.

Vashnavite themes:

Different avatars of Vishnu are depicted. Dashavatara Vishnu is one of the most popular themes. Other popular themes include:

Shaivite themes:

Temple Sculptures – Regionalisation

The temples of India emerged from a simple beginning in the Gupta age in the 5th century CE in the North and in the political centres of Kanchi, Thanjavur and Madurai in the south.

By the 7th century, Temples started outnumbering the Cave architecture. These are a source of magnificent sculptures in India. We have covered these sculptures in the chapters related to temple Architecture in India. The following characteristics can be traced in these sculptures:

- Mithun couples, River goddesses and Dwarpal on the doorways. We see a wider variety of celestials, gods and goddesses, historical or semi-historical scenes, music and dance scenes, arrays of warriors and animals and shalabhanjikas.

- Elements like Amalaka, Kalasha, and Gavayaksha produced regional variations such as in Odisha’s Kalinga style.

- Sculptural panels outside the temples became elaborate with a wide variety of themes.

- Sculptural features perfected over the centuries are brought in full display – such as Tribhanga style, sculptures protruding completely outside the picture plane, often even given a sensual appeal.

- Often interior sculptures sculpted with heavy, voluminous pillars, and lintels are engraved with fine images, often even polished. These Sculptures are not flat in relief but are depicted in three-dimensional (3D) forms. The back slabs of the sculptures are elaborated, and the ornamentations are delicate.

- Drapery and ornaments continue to be given a lot of attention.

The regional spirit asserting itself is seen in sculptural arts as well. Stylistically, schools of artistic depictions of the human form developed in eastern, western, central, and northern India. Distinctive contributions also emerged in the Himalayan regions, the Deccan, and the far south.

- A great majority of these regions produced works of art that were characterised by what has been described as the “medieval factor” by the great art historian and critic Nihar Ranjan Rai.

- This “medieval factor” was marked by a certain amount of slenderness and an accent on sharp angles and lines: The roundness of bodily form acquires flatness. The curves lose their convexity and turn into the concave.

- Western and Central Indian sculptures, Eastern Indian and Himalayan metal images, Bengal terracottas and wood carvings registered this new conception of form through the post-tenth century.

- Since these cult sculptures rest on the assured foundations of a regulated structure of form, they maintain almost a uniform standard of quality in all art regions of India.

- It is not only the cult images but non-ironic figure sculptures too, which conform to a standardised type within each art province and hardly reveal any personal attitude or experience of the artist.

- All over the country, post-Gupta iconography prominently displays a divine hierarchy that reflects the pyramidal ranks in feudal society.

- Vishnu, Shiva and Durga appear as supreme deities lording over many other divinities of unequal sizes and placed in lower positions as retainers and attendants.

- The supreme Mother Goddess has clearly been established as an independent divinity in iconography from this time and is represented in a dominating posture in relation to several minor deities.

FAQs related to Sculptures